I mentioned in the kick-off for our Mo Xiang Tong Xiu book club that I’d already downloaded a fan translation of Heaven Official’s Blessing (天官赐福 / Tiān Guān Cì Fú) before these editions were announced… which was 100% because I’d watched the single season of the animated series multiple times. I saw it first while house-sitting for friends, following an afternoon spent lounging outdoors petting their friendliest cat. I’d been craving sweetness, something fun and light—then I fell head-over-heels for the dynamic between Hua Cheng and Xie Lian. (Hard not to, frankly, with the sheer force of sensuality the animators imbued their version of the Crimson Rain Sought Flower with. Kudos to them on their labors, ahem.)

The donghua offers precisely zero contextualizing details, though, in the usual manner of adaptations that presume familiarity with the source material. Plus, I’d perceived many a fandom rumbling about how devastating (in the best way) the series gets as it goes on: multiple tiers of hidden identities, past slights and present betrayals, gender shenanigans, catastrophes and curses! I was thirsty for the actual books with all their promised glory… but due to the aforementioned PhD exams, never got around to opening that epub. So now, I’m reading the official translations instead.

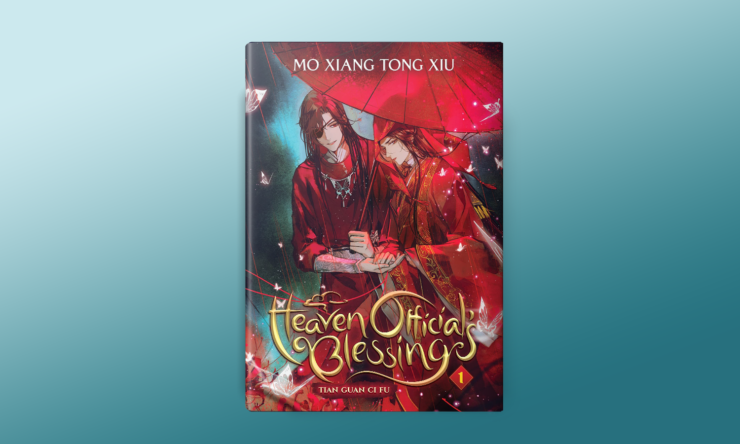

To begin, the illustrations are great—ranging from the gorgeous detail of 日出的小太陽 (@tai3_3)’s covers in lustrous color to the soft-edged cuteness of ZeldaCW’s greyscale interiors. The contrast there also encompasses, I think, the general tonal shifts of the novels themselves. I’ll admit to some curiosity about how an alternate translation for these books might’ve read, as the Suika and Pengie original is eminently consumable—but a little more workmanlike than stylistic, in terms of the prose’s flow or the literal/direct renderings of metaphor, et cetera. At its base, the translation is an accessible read without much flourish (though of course in the absence of their pre-existing efforts, we wouldn’t be getting volumes every few months—benefits and drawbacks).

But, overall, how’d I find Heaven Official’s Blessing? In a word, delightful.

On first glance, our protagonist Xie Lian has an amusing, hapless appeal. He’s the scrap-collector god, the guy whose terrible luck is notorious and whose messages to the heavenly groupchat are basically “top ten secrets for decreasing back pain!” clickbait. That initial impression, however, goes weird fast… namely because on his starter assignment after his third ascension, he’s totally chill to be abducted (dressed as a bride) by a handsome stranger who guides him through a literal rain of blood. Again, I repeat, totally chill with the blood rain. It only gets willfully weirder from there, especially in the face of his two assistants’ efforts to be like, “hey do you know who that guy is” when he makes a housemate of San Lang.

His answer is, “yeah, and so what?” In fact, when he declares his disinterest in San Lang’s human-ness (or, lack thereof) it’s a broader statement of his politics and affections:

Xie Lian crossed his own arms while being held in San Lang’s, and replied, “Forming a friendship should depend on how well two people hit it off and how well their personalities match, not their identities. If I like you, you could be a beggar and I’d still like you. If I dislike you, you could be the emperor and I’d still dislike you. Shouldn’t it be like that?”

Xie Lian is a bundle of contradictions, though. Lest we fall into treating him as a sweet lil’ cinnamon roll: remember that he’s a god—and before his descent, royalty. Furthermore, he doesn’t give half a shit about adopting a ghost king from the side of the road… and there are other moments, such as during the bride-thieving case, where we get lines like: “Xie Lian sat poised within the sedan and instructed gently, ‘Strangle them to death.'” Our protagonist is more of a smoldering fire than he appears. Sometimes it’s, well, “hard to tell whether this was a description of a god or a ghost.”

But, we wouldn’t be reading a romantic drama if we didn’t have a love interest, which brings me to our Crimson Rain Sought Flower, Hua Cheng (the ideal man?).

I find Hua Cheng’s whole deal overwhelmingly, exquisitely romantic. The shameless tenderness for his literal god, whomst he refers to with a playful intimacy from very early on as gege, runs alongside his ferociously righteous anger on Xie Lian’s behalf. He’s willing and eager to engage in unrestrained violence for the defense of a man who can’t, or won’t, defend himself. The way Hua Cheng performs devotion—affection, intimacy, protection, a refusal to allow his partner to endure needless agonies—showcases strength, cleverness, and care in a delicate balance.

Also, seriously: the cheekiness of his courtship, playing the game of “okay so, I know that you know that I’m a ghost king, but—” for almost the entire volume? Makes me yowl with delight. Hua Cheng’s version of the earlier speech about what matters most when pursuing a relationship comes in the last chapters, after this identity-reveal exchange:

Xie Lian grinned and stood up again, before turning around and casually tidying the altar table.

“All right, then. What do you want to eat, Hua Cheng?”

Behind him, there was silence. Then chuckling.

“I still prefer the name ‘San Lang.”

In their cute verbal sparring afterwards, Hua Cheng reveals a glimpse of his own insecurities—his worthiness to be companion to his royal highness, for example—obliquely, and Xie Lian dismisses them. It’s a wits-match of equals and gives an immediate sense that the arc of this relationship isn’t going to be the typical “will he, or won’t he?” Though, needs-must be acknowledged that the Heaven Official’s Blessing translation will be eight volumes in length. Hefty!

So, while the first of these slyly sets a tone that appears light on the surface, if you’re reading between the lines of other characters’ disturbed reactions or willful non-reactions to the shit Xie Lian says, you begin to sense that something isn’t quite… right.

And on that note: Heaven Official’s Blessing stands as the most mature of these series in terms of its themes and density (which, given that it’s also the most recent by date of original publication, isn’t surprising). The novel concerns itself largely with trauma, compartmentalization, and healing—as well as the nature of justice, or righteousness, in the face of a social bureaucracy guided otherwise by wealth and privilege. While Grandmaster of Demonic Cultivation shifts from revenge-tragedy to treatise on rumor, crowds, and reputation (more on that next time!), MXTX returns here to societal critique crafted through romance and melodrama with even more expertise under her belt.

Xie Lian, as a protagonist, hits closest to home for me. His neutral-positive affect comes—as the reader notices real quick—from a place of resignation to suffering and trauma. One of the first summaries of his character the novel offers, after he claims “it’s not that bad!” about an act of humiliation, is: “For someone like Xie Lian, everything besides death really was okay; he didn’t have a lot, and certainly not shame.” We see him brush off violations of his body and dignity (ranging from poisonous snake bites, to actual starvation, to being brutally murdered, to his curse shackles) with a sensationless detachment that openly disturbs Hua Cheng, “Nan Feng,” and “Fu Yao.” Obviously, his romantic arc is going to be tangled up in his habits of compartmentalization and process of recovery—which is one of the big draws of these novels.

Then, on the level of the actual mystery plots around the heavenly officials, thematic wrestling with justice and righteousness comes to the forefront. Xie Lian ponders from the start how the bureaucracy of the gods basically doesn’t listen to the common people: how wealth, or status, are prerequisites for an intercession from the heavens. We learn, later, of his youthful desire—which he is now embarrassed by, believing himself foolish—to save those common people. Several of the earlier cases he solves here are, in fact, direct results of gods’ misbehavior and dishonesty. Wonder where that’s going to go, as we delve into his repeated demotions from their ranks (as well as his continual re-ascensions).

And while it’s maybe cheating to bring up the series as a whole, I’m going to anyway for a closing teaser—because Heaven Official’s Blessing ends up being the MXTX novel that deals most explicitly with desire: the costs of its repression, of obsessions with purity and chasteness, as well as the pleasures and freedoms of pursuing queer intimacies. I’m threading the needle of ‘no spoilers for future volumes,’ but I’d point toward a big difference in how Xie Lian understands himself (or doesn’t!) as compared to our other two series protagonists. Gender doesn’t register for Xie Lian as the barrier for processing his attraction to Hua Cheng—who he’s immediately opening to pursuing a queerly intimate emotional relationship with. Instead it’s his prior refusal of all desire, being strictly held to vows of celibacy, which presents a block to approaching queer sexual intimacy for him.

Really, it should come as no surprise that I’m weak for stories where embracing queer sexuality brings joyful liberation from repression, pain, and suffering. But with seven volumes left to go from here, I’m ready to immerse myself in the (regularly meme’d) highs and lows of terror, trauma, revenge, and true love awaiting me throughout Heaven Official’s Blessing.

Rooting for you over here, Xie Lian, and for your handsome companion too.

Verdict: Most Likely to Come Up in Therapy (Positive)

Lee Mandelo (he/they) is a writer, critic, and occasional editor whose fields of interest include speculative and queer fiction–especially where the two coincide. Summer Sons, their spooky gay debut novel, was recently published by Tordotcom, with other stories featuring in magazines like Uncanny and Nightmare. Aside from a brief stint overseas, Lee has spent their life ranging across Kentucky, currently living in Lexington and pursuing a PhD in Gender Studies at the University of Kentucky.

it’s such a wonderful story!

Una vez que te sumerges en el mundo de Ti Guan Ci Fu, no podrás parar la montaña rusa de emociones, conocer por todo lo que tuvo que pasar Xie lian y mi amado Hua Cheng, de como sus historias se entrecruzan para tener esa linda historia de amor, lealtad, entrega y devoción.

I also read the fan translation and am ordering all these as they become available. The beautiful devastation of this novel… I’m so happy to see it get so much attention and hopefully this introduce more people to these fabulous novels.

Just coming here to say thank you for recognizing that Xie Lian is not some stupidly naive 800-year old god. He’s gone through a lot, yet in his third ascension he’s just like his robes – simple, humble, and clean.

I feel like one of MXTX’s strengths is building characters who are mysteries unto themselves until you understand the full breadth of their backstory. Xie Lian, I think is the most prominent example of this, and it just makes you love him more and feel so much more for his and Hua Cheng’s journey together.

Tian Guan Ci Fu es de mis novelas favoritas de todos los tiempos; no he podido recuperarme luego de haber conocido a Xie Lian y Hua Cheng porque su historia y su amor es incomparable